Whiteout Capital

Private investor publishing independent research focused on microcaps.

California Nanotechnologies (TSXV.CNO)

Published: Aug 10, 2023

Market cap: $4.54MM

FDS: 31.8MM + 6.36MM if fixed SOP resolution passes

Share price: C$0.175

FY 2022 revenue: $1.38MM

FY 2022 earnings: $79.8k

FY 2022 FCF: $537.2k

*Figures are in USD even though the ticker on the TSXV

Quick pitch

California Nanotechnologies (TSXV.CNO), or Cal Nano for short, is a company based in Los Angeles, California that specializes in two advanced material manufacturing processes—spark plasma sintering (SPS) and cryomilling. The company is growing revenue at ~30%/year and just reported its second consecutive year of both GAAP earnings profitability and positive free cash flow.

While the company is tiny, they are a leader in SPS and cryomilling technology and have spent the last decade building both technical expertise and a network of relationships with leading National Laboratories, venture-backed startups, and Fortune 500 companies via research and development projects.

I recently flew out to LA and met with Cal Nano’s CEO, Eric Eyerman, and was impressed both by what he’s been able to accomplish in his 5-year tenure running the company with virtually no resources and his future vision for the company.

Over the next few years, Eric plans to drive growth by transitioning Cal Nano from solely a research and development partner to a commercial-scale toll manufacturing services company. After nearly a decade since Eric started working at Cal Nano as an intern right out of college, he sees an adoption wave picking up steam behind which he believes materials made from their technologies will start to be incorporated into high-tech products in defense, aerospace, oil & gas, nuclear, battery, semi-conductor, cleantech, and industrial.

After visiting Cal Nano’s headquarters, I agree with Eric’s assessment and think that we are on the brink of a more general material science revolution that will enable step-change improvements to many high-tech physical processes that modern civilization depends on. Like any small company, there are immediate challenges they face, but I think they have a good chance to overcome them. With FY 2023 revenue of just $1.4MM, I see a long (and profitable) runway for Cal Nano should the industry take off like we anticipate it could.

History & management

Cal Nano was originally spun out of Omni-Lite Industries (TSXV.OML: $6.67MM), a contract fastener and component manufacturer serving the defense and aerospace industries. On February 1, 2007, Cal Nano was spun out via an acquisition by Veritek Technologies Inc., a capital pool company, and began trading on the TSXV.

I asked Eric why Omni-Lite originally decided to spin off Cal Nano rather than build it in-house. He said that he wasn’t there and can only speak anecdotally, but his understanding is that at the time nanotechnology was trendy, similar to crypto or AI more recently, and they thought they could raise more money spinning it out.

Omni-Lite still owns 18.9% of the company and has issued Cal Nano some of their outstanding debt. They maintain a good working relationship and share office space.

For many years, the company barely scraped by. They’d go long periods of time without a contract, then land something that extended their runway. They worked with large companies and prestigious National Labs, signing one-time R&D contracts and helping them set up their own SPS equipment.

As a quick interjection, I think it’s worth noting that even though the company has been around for 15 years—and for a large chunk of that time they struggled to make $400-500k/yr in annual revenue—they have issued minimal shares and today have a total share count of 31.8MM.

Let’s sidestep for a minute and talk about Eric Eyerman, the current Cal Nano CEO. Eric graduated from Rutgers with a Chemical Engineering degree in 2013. After graduation, he decided that he wanted to move to LA. He packed a suitcase and flew across the country without a job lined up, but with the hope that he’d find something related to his degree.

Upon arriving in LA, he got a temporary job at a local fitness center. It just so happened that his manager at the gym was roommates with the then CEO of Cal Nano and introduced Eric to him. In 2014 Eric started working at Cal Nano as an intern. Eric also met his future wife at the fitness center—that gym treated him well!

Over the next couple of years, Eric built up experience working at Cal Nano and running the SPS machine. In 2016, the former CEO left abruptly, which put the future of the company in doubt. There were only a few employees and they lacked a leader. At this point, Eric explored taking the experience he’d gained and using it to get a job at a larger company. He said that he had options that would have provided better benefits and pay, but that he loved working at a small company and believed in the potential for the advanced materials they were making.

Eric ultimately decided to stay at Cal Nano and immediately moved up into the COO role, followed by a promotion to CEO in 2018. Under Eric’s leadership, the company has gone from flatlined $400k revenue to $1.4MM in five years while also flipping from negative to positive earnings and free cash flow. Eric, in his early 30s, will celebrate his 10th year anniversary at Cal Nano in January 2024, and has a passion for advanced materials.

I personally think that’s a very impressive and promising management setup.

Culture

Eric was kind enough to welcome me for an entire day in the Cal Nano office. He spent the majority of his working hours and dinner after work meeting with me. We began in the morning with a brief chat and tour of the facility. They lease part of Omni-Lite’s office and space is definitely tight, but they’ve come up with creative ways to expand without leasing more square footage.

They announced recently that they acquired a new cryomill for a great price. I’m not sure where they’ll have room for it, but maybe they’ll park a second trailer back there. In all honesty, I love scrappy stuff like this.

About an hour before lunch, Eric had a scheduled call with one of their customers. He set me up in the conference room and took his call in his office. I took the opportunity to jot down as many notes on what we’d covered already, but also watched how the office operated. When he finished his call, he gathered his team, they met for maybe ten minutes, then everyone scurried out of the room and went back to work.

This was a theme I was impressed with throughout the day—for such a small company, I think Eric does a great job delegating and I could tell the company was still operating smoothly even though Eric was spending the majority of his time with me. Cal Nano is still in the “hustle” phase and Eric wears many hats, but I see early promise that he’s the type of manager that can scale a hustle into a well-oiled business. Eric said that the next role he wants to hire for is a CFO so that he doesn’t have to handle as much of the financials and can focus more on operating the company.

At the time of my visit, the company was at seven full-time employees (including Eric) and three part-time. They were also planning to hire summer interns. Two of Eric’s six full-time employees are VPs Spencer Song and Brian Weinstein, who have also been at the company since Eric’s early days as an intern. All three of them could easily make a higher salary working at a large company, but they like working at Cal Nano and believe in its potential. I think the fact that these three key employees have all been at the company so long despite its challenges and that they’ve given up career opportunity costs shows how much potential they see for Cal Nano.

The one downside I noticed with the management setup is that neither Eric nor the other two key VPs own significant stock in the company. I asked Eric why there is a discrepancy between how dedicated they are professionally to the company and their ownership of it. I sensed that he is currently working with the board to reconcile this and it’s something he’s also wanted to address. In my AGM packet I received a few days ago, there is a resolution to create a ~6MM share pool for compensation incentives. I don’t know exact figures, but I’d bet that Eric, Spencer, and Brian will soon receive substantial options grants.

Frankly, given how much these people have put into the company, I think a generous equity compensation should happen in the near future. If Cal Nano succeeds, they should benefit.

Products and services

I’m going to start with an overview of the two technologies they specialize in, then circle back around and explain how it all comes together.

Spark plasma sintering (SPS)

Most metal components in industry are currently made using a process called hot pressing. This method involves placing a powdered metal (sometimes so fine particles are less than a nanometer across, hence the term nanomaterial) into a mold and using a combination of pressure and inductive heat to mold the particles into a solid mass without reaching the liquefaction temperature. This process of turning powdered metal, ceramics, or plastics into a solid without liquefaction is called sintering.

Taken from the hot pressing Wikipedia page, a basic example of sintering with heat is pressing two ice cubes together until they form a solid. An example of sintering with pressure is cars packing snow on the road into ice as they drive over it.

In modern manufacturing, most metal components (depending on their physical properties) are either made from liquifying metal and pouring it into a mold, pounding it into the desired shape, or hot pressing it. The hot press method is preferred for metals with high melting points because it takes a lot of energy to liquify them and they are generally too brittle and hard to be pounded out.

On the quality side, one of the major disadvantages of hot press sintering is that you pour powder into a mold and then heat it from the outside to sinter it. Since the heat must distribute from the outside to the center, this can be a long process and heating is often uneven, leading to suboptimal results.

One of the cool aspects about sintering is that when you start from a powder and don’t melt the particles into liquid, you have more control over the grain structure of your final material, which allows you to optimize various properties, such as thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, hardness, and more.

Now with that background, let’s talk about SPS. This technology has actually been around since the 1960s and it’s been used occasionally in Japan for some time in commercial settings, but for whatever reason, it never took off in the West and is rarely used in industry today. Eric thinks that this is because Japanese companies have held this technology very close. Even among Cal Nano’s customers, many treat the fact that they are using Cal Nano to explore SPS technology as a trade secret and don’t let Cal Nano name their company.

The main difference between hot press sintering and spark plasma sintering is that rather than using inductive heat to coerce the powder into a solid, SPS uses an electrical current. If you picture two ping pong balls pressed against one another, the surface area where they actually touch is pretty small. This is similar to the layout of particles when running SPS. When electricity runs through the powdered particles, the current is much higher at the bottlenecks where particles touch, causing electrons to be jammed together as they cross from particle to particle. The result is uneven heating whereby only the particle edges that are touching slowly melt together. As this occurs, more space opens up for electrons to flow through and the particles cool down before melting them all the way together.

The second you turn on the SPS machine, electrons flow through every particle in the mold and not only does it heat more evenly than inductive heat, since you don’t have to wait for heat to distribute from the outside into the center, the process is significantly quicker and cheaper. These are the main reasons why electricity is superior to inductive heat.

In general, Eric said that with metals they have observed the ability to increase hardness by a factor of two using SPS versus hot press. You can also mix metal and ceramic powders to achieve unique properties. I’ll go over some example projects later on that will highlight what SPS can do.

From an economic point of view, SPS is up to 10x faster than hot press sintering and uses significantly less energy. This is a step-change improvement over hot pressing.

Cryomilling

Sometimes customers send Cal Nano the raw material already in processed or partially processed form. Other times, they make the powder themselves. They do this with a process called cryomilling.

The basic idea is that you put your material into a steel mill filled with liquid nitrogen, which freezes it and makes it more brittle. As the mill spins, it breaks down the material into smaller and smaller pieces, sometimes less than a nanometer across. You can control the size you break the material down into, which enables you to achieve different properties later on in SPS.

Since the process takes place in liquid nitrogen, they can also work with materials that are typically dangerous and difficult because of their sensitivity to oxygen, heat, and moisture.

Cal Nano also has customers who pay them just to cryomill material. One example Eric gave me is a biodegradable plastic company they work with. A recent positive development in 2023 is that the team was able to purchase a used cryomill at a good price that will triple their current milling capacity.

Furthermore, Cal Nano was also recently awarded a patent for a manufacturing process to cryomill at scale, which hasn’t been attempted before.

The full process and sales cycle

Now that I’ve explained the basic technologies Cal Nano specializes in, here is a summary of the full process from order to fulfillment.

A typical planning period with a customer includes about a week of programming after signing a contract. The customer then sends Cal Nano the raw material.

Typically 3-4 weeks later, after they’ve received the raw materials, they start the program.

The first step is to cryomill the raw material if it is not fully processed. This often involves breaking it down into a specific size and shape to achieve a desired outcome later in SPS.

Generally, it takes less than an hour to SPS a component and a couple of hours after for it to cool to the point that it can be handled without safety equipment.

The component is then removed and machined into the final shape with various pieces of equipment.

Sometimes there are also secondary SPS steps where they might SPS a new material onto the outside of the initial component as a coating. Or they may SPS two components together.

It typically takes them about a week of experimentation to perfect a specific component and send it off to their customer.

Customer rap sheet

Speaking of customers, Cal Nano has an extremely impressive network of paid customers for their size. They generally sign NDAs and aren’t allowed to talk about specific projects, or sometimes even name companies, but here are a few of their previous clients they can mention:

- TSMC

- Ambri

- Tesla

- Raytheon

- NASA

- Boeing

- GE

- Sandia National Laboratories

- Idaho National Laboratory

- Adidas

- Bloom Energy

- Leading startups in the green tech space

- Large companies in the oil and gas industry

Much of the benefit of the components Cal Nano makes is not visible as the goal for projects is often to achieve exceptional durability from stress, heat, corrosion, etc.

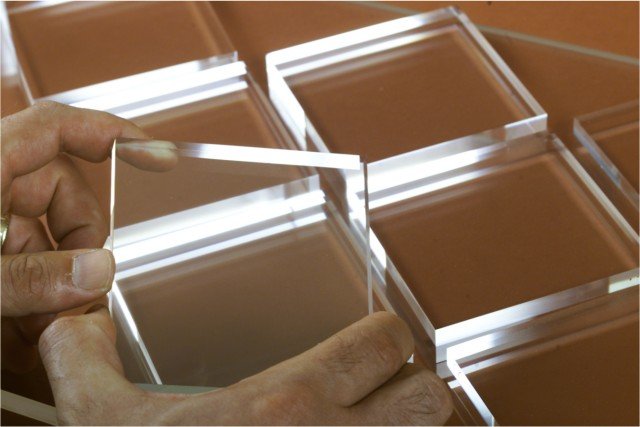

Here are a few of the more visible examples of products they’ve completed.

What’s interesting about this is that SPSing multiple pieces together like this forms a bond between them that is generally stronger than the rest of the material. This is the opposite of welded components where the bond line is typically where the component will fail. Eric said they’d done extensive testing and whenever they SPS multiple components together—for example, four-cylinder pieces to form a longer cylinder—and then do a stress test, the component almost never breaks on the bond line where the components were SPSed together, it generally breaks at the midpoint between two bonds.

This is important to note because a component is only as strong as its weakest point, so even if in testing the solid piece of a component made using SPS is two times stronger, the actual advantage is larger for multi-piece components because you can also then SPS them together instead of welding or other heat-based processes that introduce weak links.

Before moving on, I want to mention one customer that I don’t have visuals for, but that Eric thinks could be a near-term catalyst for the company.

Cal Nano recently PRed a longer-term contract with a leading green steel company. Up until now, Cal Nano has mostly been an R&D partner. While many large companies have toyed with some of these advanced material science methods through small projects, very few have implemented it in industry and installed these components into real products at scale.

Eric sees this changing in the near future and thinks that he can position Cal Nano as a toll manufacturer. This contract with the green steel company is their first big breakthrough on this front and has the potential to be a major tailwind for Cal Nano if the steel company is successful.

Competition

As of right now, Cal Nano has no direct competitors in North America. As outlined above, SPS in particular is a nascent technology that is only beginning to be used. Outside of national labs, who are focused on academic research, Cal Nano is the only commercial company servicing customers in North America with custom SPS and cryomilled components.

In Japan, there are companies with similar business models that have existed for decades, but they have never made the leap across the Pacific. There is also one company in Europe called Norimat that is attempting to do what Cal Nano is doing, only for European industries. Cal Nano considers them a close partner and the two have collaborated for many years.

When I asked Eric what their competitive advantages are, he said that he considers the network they’ve built throughout the industry over the last decade to be the company’s most valuable asset. They’ve partnered with many universities and National Laboratories over the years, and now the people they worked with have spread out to various companies and are interested in bringing the R&D work they did with Cal Nano into industry where they are now decision makers.

Another common way they connect with new customers is through the work they’ve done with National Laboratories and universities. Companies approach these labs asking about advanced material technologies and the labs refer them to Cal Nano.

There is also a lot of built-up expertise on their team, particularly in SPS. While the process might sound relatively simple, it’s challenging to take customer performance requirements and engineer a finished product. Simply achieving a solid component with no powder left takes a good deal of skill and knowledge. Then you have to know what materials to use, how to process them into a powder, how to run the SPS to achieve a specific set of goals, and often there are shaping or other secondary processing steps required to ship a final product.

While Cal Nano is the dominant player in a niche area right now, it’s probably unrealistic to assume they will maintain a monopoly if these advanced material processes do take off. With that said, Eric views Cal Nano as an opportunity to bring SPS to North America, even if they don’t take 100% market share. This is why they are also an exclusive sales and servicing partner with Fuji-SPS, a leading SPS manufacturer out of Japan.

Eric said that some companies, such as SpaceX, want to do everything in-house. And rather than try and force them to use Cal Nano by withholding information about the process, he’d rather sell them a machine and do some R&D work to help get them going. This gets their foot in the door and will likely lead to future work either with that company, or with future companies as employees move around. Eric thinks the industry will eventually be very large and wants Cal Nano to be a major contributor to the technology improving important products in our modern lives.

For every company that wants to buy an expensive machine, hire multiple specialized employees, and put in the time required to perfect a technology outside of their core competencies, there will be ten companies that want to replace a single component in their product with something more advanced and they will likely be perfectly willing to outsource manufacturing to Cal Nano.

I think it’s unlikely for a competing business to pop up in North America with an identical business model. If there was a funded startup that wanted to enter, they’d likely have to pick one product to manufacture, perfect it, and then start making it at scale and attempting to sell it. Even then, this type of business model doesn’t typically attract venture capital because it’s capital intensive and there is no existing market to attack, you have to create it. Without a vast network of connections and a strong reputation (like the one Cal Nano has), it’d be very difficult for a startup to land a contract with a large company pre-product.

Unit economics

One of the aspects of Cal Nano’s business model that I love is that on the one hand, they are making cutting-edge components to be installed on some of the most advanced technology the human race has ever created—nuclear fusion reactors, spaceships, semi-conductors, etc.—but at the same time, even if they make 60% gross margins, the cost of the component as a percentage of the overall end product will be tiny.

For most companies, I think it will be a no-brainer to buy components from Cal Nano rather than manufacture in-house because the incremental cost of switching from a traditionally-made component to an SPSed component in absolute terms will likely be small, and the fixed costs required to start an SPS facility in-house will likely not make economic sense.

Now let’s drill down into the unit economics of the SPS and cryomilling machines.

An SPS machine costs around $1.5MM plus $40-50k of modifications and can conservatively generate $1MM/yr in revenue at 60% gross margins. I think potential revenue could actually be quite a bit higher, but it will depend on what exactly they end up manufacturing.

On the cryomilling side, a machine costs $250k plus $40-50k of modifications and can also conservatively generate $1MM/yr in revenue at 60% gross margins.

Cryo-milling economics are more favorable because the upfront fixed cost is so much lower, but there are fewer potential projects that are pure cryomilling.

Let’s focus on SPS first. Using conservative estimates, I think each machine doing $1MM/yr in revenue at 60% gross margin and 30% EBITDA margin is realistic. That’s $300k in EBITDA, which means the machine will pay for itself in five years, which would compound invested capital at ~15%.

A high-end bound for a machine would probably be in the $5MM/yr ballpark. If we take the midpoint between our conservative and high-end estimates, we get $2.5MM of revenue generating $750k EBITDA at our stated margins, which means each machine will pay for itself in two years and compound invested capital at ~42%.

Cryo-milling is even more attractive on a unit economics basis. Just $1MM in revenue generating $300k in EBITDA would pay for the machine in one year, or 100% return on invested capital.

Cal Nano currently has spare SPS capacity to do about double the revenue of what they are currently doing, so capital is not needed imminently to keep the R&D business growing. On the cryomilling side, they just purchased a used machine that will allow them to 3x their current capacity. One of the things I love about Eric’s management style is that when he sees a good deal (like the cryomilling machine) popup, he pounces and is planning ahead for two years from now rather than optimizing financials for this quarter. This is one of the many ways that he’s demonstrated his resourcefulness and long-term planning.

The numbers above are EBITDA, so it’s worth talking about the DA a bit. I asked Eric what the useful life of an SPS machine is and he said that SPS machines in general have been in production since the 60s and we still haven’t hit a point where machines are breaking down. They of course require repairs, but overall they are extremely durable and don’t have many moving parts that can break catastrophically. Cal Nano’s oldest machine is from 1998 and it still works fine.

So while they are required to depreciate these machines fully over 7-10 years on their balance sheet, it’s likely they will far outlive that.

Furthermore, since Cal Nano has exclusive sales and servicing rights to sell Fuji-SPS machines, they are the experts anyone in the US would call to fix their machine if it does fail. They’ve gotten very good at fixing the machines and costs for them to maintain would be significantly less than any competitor or potential customer bringing the technology in-house.

Challenges

While I think Cal Nano has a bright future, they are still a small company with material risks.

Cal Nano has $1.44MM in debt issued by Omni-lite, the company they were spun off from and share an office space with. The loan is callable and if they were to call it, Cal Nano would go bankrupt overnight. Cal Nano plans to start making $10,000 monthly principal payments (in January they did a one-time $120k principal payment), but given the size of their debt, this will barely scratch the surface and they will likely need to renegotiate or refinance elsewhere.

I believe the loan being called is unlikely because the two companies continue to have a good relationship. Omni-lite owns 18.9% of Cal Nano, so if they were to call the loan, they’d be incinerating more value in Cal Nano stock than they’d ever get back from a bankruptcy and liquidation. This is still something to keep an eye on, especially if Omni-lite starts selling shares. It’s also worth noting that Roger Dent is a director of both Cal Nano and Omni-lite and has material holdings in both.

The unfortunate thing is that this debt pre-dates Eric and was used mostly to keep the lights on during lean years when they used to go long stretches between contracts, it wasn’t even converted into a usable asset.

The other near-term challenge is that Cal Nano will need a larger SPS machine to make the switch from R&D partner to a commercial-scale toll manufacturer. I think it’s unlikely they will be able to do this without outside funding and that it will most likely involve a combination of sources which will likely include a dilutive capital raise.

After this next equipment purchase, I think they will likely be able to fund the company’s growth organically without further dilution. Eric expressed intent to minimize dilution in the long term, but did not rule out a short-term raise.

In the AGM packet I received a few days ago, there is a proposal to loan Eric $250k during the next equity raise and this resolution would expire one year after passage. The funds would be used “for the purchase of common shares,” and Eric would pay Cal Nano a fair market interest rate on the loan.

This signals a few things to me. First, Eric is extremely bullish on the company’s prospects and wants in as soon as possible. He doesn’t want options, he wants to own shares. His salary was $120k in 2022 and $165k in 2023, which is pretty modest given that he lives in LA. A $250k loan is substantial relative to his income.

Second, a dilutive financing is coming. This loan resolution expires one year after it’s passed. If I dig a little deeper and read between the lines, I think it’s most likely that the company will only raise if they need to for growth (ie new equipment), and the only reason they’d need new equipment is because they’ve landed their first toll manufacturing customer. It’s possible that they are close to landing their first big contract and afterwards they plan to raise to fund the expansion necessary to deliver.

If you’re the type of investor that will not tolerate any dilution, this company is probably not for you. There’s a chance that the price drops after they announce a contract and raise depending on how dilutive it is. The nice thing is that the money will likely be used to purchase an SPS machine, and those machines hold their value. So there will be dilution, but the cash should be converted into a fairly durable asset. I have personally chosen to buy now because I believe in Eric and what Cal Nano can do long term and the stock is too illiquid for me to take a reasonable position quickly after a major announcement.

On the product side, I think that corporate risk aversion is a near and medium-term risk. I have a close friend who works at a large defense contractor and I know that they are typically resistant to swapping in even something as simple as a new screw on a product they’ve been making for 50 years because nobody wants to be the person who fixed something that wasn’t broken, which led to a catastrophic failure on a billion dollar piece of equipment. In the long run, I think companies in all industries will have no choice but to keep up with technology or get left behind. For Cal Nano, it’s mostly a question of timing. Is Cal Nano at the right place at the right time, or are we still ten years too early?

Finally, while they’ve found success doing R&D work, they are on the brink of transitioning their entire business model to toll manufacturing. Anytime you change directions that much, there are risks that things won’t pan out as planned.

Conclusion

Cal Nano is a growing and profitable company with promising management and the ability to invest into a defensible business at high returns on invested capital. They’ve spent the last decade building up expertise in nascent advanced material technologies and growing their network of customers and partners. While they are a microscopic company by public market standards, they are already a trusted partner to many leading startups and Fortune 500 companies that produce some of the most advanced products in existence.

I’ve enjoyed my conversations with Eric and am constantly impressed by how much vision he has. In the short term, he’s laser-focused on landing the first toll manufacturing customer, hiring a CFO to take more non-technical work off his plate, and figuring out how to fund their growth. In the long term, he talked about how he envisions possibly opening a manufacturing plant in Texas where energy is cheaper and they’d be more centrally located to their customers. At dinner, we even pondered some of the other technologies Cal Nano could move into beyond SPS and cryomilling, but that’s a topic for further down the line.

If Cal Nano can successfully shift to toll manufacturing and get the ball rolling, I think they have the momentum to carry them forward for a long time and that this company could have a long and profitable growth runway.

Resources

If you want to learn more about Cal Nano’s technologies, check out the Materialism Podcast. Eric was a guest on episode 63 and they go over SPS. I’d recommend starting with episode 35 as they go into the history of SPS and give a more foundational background.

The Sintering Wikipedia page also does a good job of explaining how the process works.

Disclosure

I own shares of Cal Nano at the time of writing and may buy or sell shares at any time without notice or warning. This write-up contains my thoughts and opinions and is not investment advice. I may have made mistakes. Do your own due diligence and review my legal disclaimer.